Flower Remedies Can Help Hasten

Our Purification and Enlightenment

Theosophy Magazine

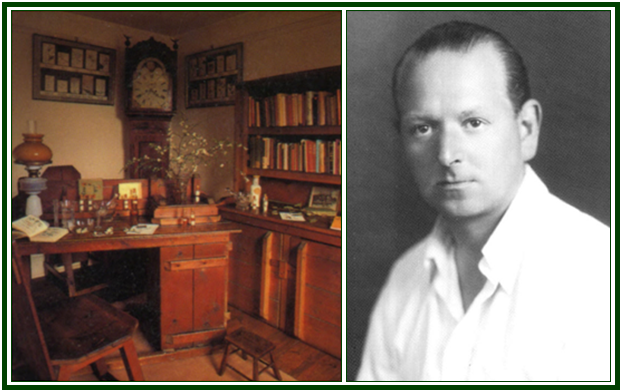

Edward Bach, and his Office

00000000000000000000000000000000000000

Reproduced from “Theosophy” magazine,

Los Angeles, April 1951 edition, pp. 245-251.

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000

“Disease is a kind of consolidation of a mental

attitude and it is only necessary to treat the

mood of a patient and the disease will disappear.

The remedies of the meadow and of Nature,

when potentised, are of positive polarity; whereas

those which have been associated with disease

[such as bacterial remedies] are of the reverse type…”

(Edward Bach)

One early morning in May, 1930, his biographer relates, as Bach “was walking through a field upon which the dew still lay heavy, the thought flashed into his mind that each dewdrop must contain some of the properties of the plant upon which it rested; for the heat of the sun, acting through the fluid, would serve to draw out these properties until each drop was magnetised with power.”

The thought-flash had come to a physician amply qualified to make practical use of the principle involved. It may well have been a reminiscence brought through from former lives, for even as a child Edward Bach [1] had been motivated by the conviction that there must be a simple form of healing which would cure all kinds of disease. He early and all during his life manifested that love of nature and of his fellow men, which was to culminate in his discovery of the healing faculties of the common herbs, flowers and trees so abundantly provided for man by Nature. As a boy in school, it is said, “He would also dream that healing power flowed from his hand and that all whom he touched were healed; and these were no schoolboy flights of imagination, but the inner knowledge of what was to come to pass, for ….. in after years he came to know he did indeed possess the power to heal, and many were the sick folk who were cured by his touch.”

The years between the dream and its accomplishment are briefly and simply recounted in the book from which these passages are taken: The Medical Discoveries of Edward Bach, Physician, by Nora Weeks. Born in an English village in 1886, Edward Bach enrolled in Birmingham University at the age of twenty, and by 1914 had completed his medical training. He had decided to study all known methods of cure, but while practising, in turn, as a pathologist, bacteriologist, and homeopath, he never relinquished his aim of finding pure remedies to replace the complicated form of treatment which, for all their scientific validity, could offer no certainty of cure. Spending hours in hospital wards, he “saw how the process of healing was often painful, sometimes almost more painful than the disease itself, and this served to strengthen in him his conviction that true healing should be gentle, painless and benign.”

From the commencement of his career, Bach was searching for a more accurate and precise approach to diagnosis and treatment than ordinary medical methods afforded:

“As a medical student Edward Bach spent little time with his books; even then he felt that theoretical knowledge was not the best equipment for a physician, nor the perfect method of dealing with human beings who differed so greatly in their reactions to the diseases which affected their physical bodies.”

“To him the true study of disease lay in watching every patient, observing the way in which each one was affected by his complaint, and seeing how these different reactions influenced the course, severity and duration of the disease.”

“Through his observations he learnt that the same treatment did not always cure the same disease in all patients; for although perhaps five hundred persons, affected by a similar complaint, would react much the same way, yet there were thousands who reacted in a different manner, and the same remedy which would apparently cure some had no effect upon others.”

“Thus early in his search he had gained the knowledge that the personality of the individual was of even more importance than the body in the treatment of his disease.”

This perception recalls the philosophy of Paracelsus, who taught that “there is a great difference between the power that removes the invisible causes of disease, and which is Magic, and that which causes merely external effects to disappear, and which is Psychic [2], Sorcery, and Quackery.” (An interesting reversal of positions, for Paracelsus to consider that form of medicine which works solely with “external effects” as simply a form of Quackery!)

Bach had been serving as Casualty Medical Officer at University College Hospital, but he left his position and ventured into the field of bacteriology. He took with him his faith in his own intuitions, even when they conflicted with orthodox dicta, and he maintained his conviction that the personality of the patient was at least as important, if not more important, than the specific disease he suffered from. Concentrating on those chronic diseases which had hitherto defied the best efforts of the medical profession, Bach felt that he was on the track of a fundamental line of treatment when he discovered that persons suffering from chronic diseases had also a greatly increased number of certain bacteria present in the intestines.

After considerable investigation, Bach became convinced that a vaccine made from these intestinal bacteria and injected into the patient’s blood stream would cleanse the system of the poisons causing the chronic disease. While the results he obtained were “beyond all expectations”, he himself was dissatisfied with the injection method. Contacting Hahnemann’s Organon a few years later, however, he found himself in harmony with the homeopathic philosophy, and thereafter used the homeopathic system of preparation, administering his medicines orally.

Bach also succeeded in isolating seven distinct classes of intestinal bacteria and found, by working out the personality type in which certain bacteria predominated, that the bacterial groups corresponded to seven different and definite human personalities. This discovery naturally changed his method of diagnosis from one of physical examination of the disease, to a “mental” examination to determine the personality pattern of the patient. Miss Weeks remarks that “even at that time he was not at all pleased if he could not recognise the remedy a patient required in the time it took that patient to walk from the consulting room door to his desk.” Paracelsus, we will remember, made the same point, saying that if a physician knows nothing more about his patient than the patient himself tells him, he knows very little indeed. (We are informed by Miss Weeks that Bach had read Paracelsus with interest and profit.)

Although increasingly good results were obtained from his oral vaccines, named the Seven Bach Nosodes (which were enthusiastically received and used by allopaths and homeopaths alike), Bach himself desired more than a system of curing which employed the products of disease. In 1928 he began his studies in natural remedies, and put his whole faith in the healing powers of common herbs and flowers. At the age of 43, he resigned his profitable and highly- reputed work with the vaccines and devoted himself to devising a pure and effective method of potentizing herbs, committing himself utterly to his intuition that this was the right course to follow. Miss Weeks relates that he made a large bonfire of all the pamphlets and papers he had written on his former work, “smashed his syringes and vaccine bottles, throwing their contents down the laboratory sink.” Hereafter, Bach was to make no charge for his healing work, for he felt that what Nature gave so freely, he should likewise dispense without charge. This was his practice, henceforward, no matter what hardships it occasioned him personally.

Impelled by his own intuition, Bach joined the ranks of the mystics of all ages, among whom has ever prevailed a sense – when not a knowledge – of the unknown potencies of plants and stones. This knowledge is termed by H.P. Blavatsky a branch of Magic, and she wrote in Isis Unveiled (Theosophy Co., vol. II, p. 589):

“There are occult properties in many other minerals, equally strange with that in the lodestone, which all practitioners of magic must know, and of which so-called exact science is wholly ignorant. Plants also have like mystical properties in a most wonderful degree, and the secrets of the herbs of dreams and enchantments are only lost to European science, and useless to say, too, are unknown to it, except in a few marked instances, such as opium and hashish.”

The first three herbal remedies (Mimulus, Impatiens and Clematis) that Bach discovered, however, were incapable of producing as good a result as his vaccines did, and this he attributed to a difference in polarity, the vaccines possessing the required negative polarity, while the herbs were undesirably positive. That he considered polarity as an important factor is evident from his definition of disease: “Science is tending to show that life is harmony – a state of being in tune – and that disease is discord or a condition when a part of the whole is not vibrating in unison.” Theosophical students will recall that the subject of plant and mineral polarity is referred to in Isis Unveiled (vol. I, p. 137), where H.P.B. speaks of the varying susceptibility of both plants and animals to different rays of the spectrum, and terms these “differently modified electro-magnetic phenomena.” Space is given also (vol. I, pp. 264-265) to the polarity of precious stones.

How Bach finally discovered in a “flash” the secret of reversing the polarity of his remedies suggests his almost magical rapport with Nature. He collected from flowers sun-magnetized dewdrops, and so delicate were his sense perceptions that he was able to feel the vibrations and power emitted by any plant he wished to test, and his body reacted instantaneously. Miss Weeks tells us that “If he held the petal or bloom of some plant in the palm of his hand or placed it upon his tongue, he would feel in his body the effects of the properties within that flower. Some would have a strengthening, vitalising effect on mind and body; others would give him pains, vomitings, fevers, rashes and the like.” Toward the end of his life, he gained his last group of remedies in an entirely different way:

“For some days before the discovery of each one he suffered himself from the state of mind for which that particular remedy was required, and suffered it to such an intensified degree that those with him marvelled that it was possible for a human being to suffer so and retain his sanity; and not only did he pass through terrible mental agonies, but certain states of mind were accompanied by a physical malady in its most severe form.”

Since the laborious collection of individual dewdrops would be impractical, Bach evolved a new method of potentizing. He chose the best and brightest flowers of a field and floated them in a glass bowl filled with water (preferably from a clear stream nearby). When the flowers had stood in full sunlight for several hours of the morning, the water was impregnated with the power of the plant. Since the tincture thus obtained is prescribed in drops, one supply may last a life-time. A suggestive illustration of the absorptive powers of water is found in H.P. Blavatsky’s book Transactions of the Blavatsky Lodge (Theosophy Co., pp. 143-144), where she describes ice as a “great magician, whose occult properties are as little known as those of Ether.”

Bach’s final philosophy, as summed up by Miss Weeks, deserves to be quoted at some length, for the truly phenomenal success of his Remedies in curing disease is squarely based on these premises:

“A small worry passing through the mind will cause a look of strain to appear upon the face, so a continued large worry will have a correspondingly greater effect upon the body; but in both cases so soon as the worrying thought has been removed and the peace and happiness of the mind restored, all the ill effects upon the body will go also.”

“Physical disease, being merely the results of the disorganisation of the function of the brain caused by such moods as worry, fear, shock, strain, was but a symptom itself, and therefore was no indication for the treatment a patient required. (…) ”

“Recognition of the fact that moods and states of mind were alone responsible for ill health would do much to dispel the fear of disease and of the dreaded names given to certain of them, so prevalent amongst both the sick and the healthy. Then, with the patient’s cooperation, his earnest desire to get well, there could be no incurable or chronic diseases, for fear of disease is one of the chief obstacles to be overcome in sickness, and the greatest hindrance to recovery.”

“The property of the new remedies would be that of so revitalising the whole personality that the patient would easily shake off his fears and worries, and with them the disease from which his body suffered.”

“The remedies used in medicine relieved the physical symptoms of disease, but they did not remove the underlying cause – the mood – and the patient was left without help to rise above his mental troubles. For most this was not easy, and for some almost impossible; hence the long-continued suffering of so many.”

“In acute disease, the result of violent or quickly passing moods, the disorganising effect upon the body was soon over; but when the mood was not so rapidly dispelled the disorganisation continued, gaining a stronger hold upon the organs and tissues, and the after-effects might become permanent, resulting in ‘chronic’ disease.”

“Yet even the so-called chronic and incurable diseases would clear up once the mind and brain regained their normal and wise control of the body.”

Edward Bach’s life was considerably shortened by his work, and so rigorous had been the demands on his final laboratory – his own body – that he died in 1936 at the age of fifty. In all, he had sought and found thirty-eight healing herbs, and he did not leave before fulfilling his aim of providing the layman with a simple method of preparing pure natural remedies for his own use. [3]

It is not much to say that Nora Weeks’ brief volume will be gratefully received by many students of H.P. Blavatsky and William Q. Judge, especially by those who wish to understand the laws of man’s connection with Nature and the powers exercised by human thought and feeling. Merely to read of the wholesome experiments carried out by Bach and continued by many who have benefitted from his discoveries, does much to restore one’s faith in man’s kinship with the greater universe. Bach was undoubtedly a mystic and a magnetic healer, for on numerous occasions he cured diseases by the laying on of hands, and Miss Weeks records many instances of the clairvoyant powers that seemed to blossom in him after he left his orthodox medical practice and retired to live and work with Nature. It is significant – and fortunate – that Bach did not rest with powers which were peculiarly his own and non-transmittable, but persevered in his attempt to uncover a system whereby each man could be his own physician and cure self-imposed sufferings.

The essentially philosophic approach of the Bach method is evident in the emphasis on the patient’s mental outlook as the determining factor in physical disturbance or disease. It is impossible to read The Medical Discoveries without realizing more deeply that a fundamental philosophy – a science of life – is the foremost remedy for human ills of whatever nature. All else may temporarily alleviate, the best of medicine will restore the patient “to himself” simply, naturally, and directly, but self-knowledge alone can cure. The Bach Remedy News Letter reiterates Dr. Bach’s central thesis that it is the patient who has the disease, and not the disease which has the patient. From this it follows, and experience has shown Dr. Bach and his “Team”, that “the time taken for a patient to show improvement depends upon the patient and not upon the nature of his complaint.” There is no attempt to invade the integrity of another, for Bach declared: “Flower healing demands no delving into the patient’s sub-conscious in an endeavour to drag to the surface the object of his fears. People fear many different things, but it is the fear that counts….. The patient’s mood is usually indicated by his reaction to his physical complaint; work on that and administer the appropriate Remedy.” The Bach theory of health may be epitomized in his own words:

“Illness and disease, if we can only look at it aright, is a healing process of refinement and purification. If we can look at it in this light, it loses its terror. The Herbs are given to hasten our purification, our enlightenment, and hence, the work of illness being done, we can return to health.”

NOTES:

[1] A Welsh name, pronounced baych. (Note by “Theosophy” magazine)

[2] A 2017 NOTE: “Psychic” and not “Physic” as Franz Hartmann wrongly has it, in a book from which Theosophy magazine seems to have taken the quotation. We follow Alexander Wilder, instead of Hartmann. See Wilder’s article “Animistic Medicine” in “Metaphysical Magazine”, vol. 21, no. 7, November, 1907, pp. 385-394. The quotation will be found at p. 387. The magazine is available online. (CCA)

[3] The two short works entitled Heal Thyself and The Twelve Healers are concise herbal manuals and have been kept in print by C. W. Daniel Co., Ltd., which is also the publisher of The Medical Discoveries of Edward Bach, Physician. “Dr. Bach’s Team”, located at Mount Vernon, Sotwell, Wallingford, Berks, England, carries on his work, and began issuing, in March 1950, The Bach Remedy News Letter. This small periodical – a quarterly – contains amplifications of Dr. Bach’s theory and practice, together with reports of the work being done with his remedies in all parts of the world. The editors of the News Letter state, for example, that the Bach remedies “have been proved instrumentally to carry definite and measurable radiations. (All things are in a constant state of vibration, each with its specific vibratory rate.) There are some Practitioners who prescribe the Remedies radionically, others by means of radiesthesia.” (Note by “Theosophy” magazine)

000

On Paracelsus, who is mentioned several times in the above article, see in our associated websites the article “Paracelsus and the Book of Nature” (by Carlos Cardoso Aveline) and the short story “The Rose of Paracelsus” (by Jorge Luis Borges).

Read in our associated websites the booklet “Health and Therapy”, of various authors, and the articles “Food as Sacrifice”, “Mahatma Gandhi’s View of Food” and “The Meals of the Pilgrim”.

000