A Pioneer Who Helped Preserve And

Spread the Original Teachings of Theosophy

Spread the Original Teachings of Theosophy

Carlos Cardoso Aveline

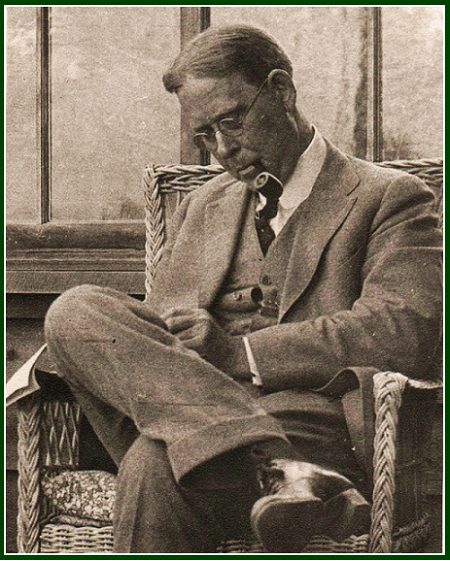

This is the only known photo of John Garrigues.

It was taken at some point between 1919 and 1925.

Independent research on the history of the esoteric movement shows that John Garrigues (1868-1944) was one of the main 20th century theosophists and authors.

One of the founders of the United Lodge of Theosophists, Garrigues kept his writings anonymous during all his life. For decades after his death his name was unknown, except to those who had met him personally or had heard of him by direct oral testimony.

The silence was broken in a gradual way. Gabriel Blechman’s notes on him were published in October 2001 at “The Aquarian Theosophist”. Since 2011, our associated websites offer their readers a selection of his texts, in more than one language.

The writings of John Garrigues are only partially identified. For many years he was the main editor of “Theosophy” magazine, and the short length of some of his best articles can be explained by the editorial need to supply a final article of some precise size, in order to close the edition of a magazine.

Looking at the Movement as a Probationary Field

As his texts in “Theosophy” were anonymous, we must share the criteria used in identifying and selecting them.

These are ten main identifying characteristics of articles by JG:

1) No fear of looking at obstacles. He presents the theosophical effort as a sacred but dangerous enterprise to be serenely understood. It is the journey of the hero, and moral courage is necessary in it.

2) A clear vision of both past and future of the theosophical movement. Having a clear understanding of the law of cycles, Garrigues shares the results of his long-term research on the effort done by Initiates. He consciously worked towards a better future, whose basic lines were known to him.

3) The facing of trials. He discusses the probationary path and the challenges which every aspirant to discipleship has before himself, as in the article “The Hour of Need” (“Theosophy”, May 1921), which is also available at our associated websites.

4) A living presence of contrast. JG examines the contradictory aspects of life, while showing also the presence of equilibrium and symmetry in every aspect of Reality.

5) An often poetical viewpoint. This is easy to find in his book “From the Book of Images”, and many of his other writings.

6) An axiomatic style. Garrigues’ articles have often short sentences ready to be meditated upon. As an example, one can see in our associated websites the article “The Key to Steadiness”.

7) A clear examination of the challenges facing the theosophical movement. JG frankly discusses pseudo-theosophy and shows how it works, paving the way for the roots of self-delusion and collective illusion to be eliminated.

8) An active defense of H.P. Blavatsky and W. Q. Judge. One of the occult reasons why such a task has a decisive importance is that the skandhas or karmic records of the founders’ lives are at the very center of the aura of the movement. Garrigues also developed a correct viewpoint as to H.P.B.’s living influence after her physical death in 1891. One example can be found in the text “How Far Away is H. P. Blavatsky?”, which is available in our websites.

9) A perception of strategic choices. The metaphor of the war and the warrior is easy to find in Garrigues’ writings. One example is the article “The Law of Retardation” (“Theosophy”, November 1920) – which is published at our associated websites. Another one is “Survey of the Armies” (“Theosophy”, August 1922). Classical use of the Warrior metaphor can be seen in the “Bhagavad Gita”, the “Mahatma Letters”, W.Q. Judge’s text “Hit the Mark”, and in the writings of H.P. Blavatsky – besides the New Testament (Matthew, 10: 34) and other ancient and modern texts.

10) An observation of personal motives. JG studies the emotional alchemy necessary to make real progress along the way. He gives useful hints as to developing, strengthening and purifying one’s spiritual Will. His motivational articles are typically short.

Other factors may be added to the list. Among them, the choice of words, style, rhythm of sentences and mantramic elements present in contents and form.

Developing the Right Intention

Since the 1890s the theosophical movement has remained unnecessarily small or grown in wrong ways. The vitality of the movement depends on the inner motivation of its members. One of the stumbling blocks consists of a pair of opposites: on one hand, there is the illusion of personal ambition; on the other hand, the illusion of personal lack of motivation. The paradox results from an absence of proper information regarding the nature of the movement.

Well-informed people see Theosophy as both stimulating and realistic, challenging and sober. Philosophical knowledge must be open to critical examination. The theosophical Pedagogy may be defined as the art of independently researching and teaching esoteric philosophy. One can see how it works by studying “The Mahatma Letters” and “Letters From the Masters of the Wisdom”. The Letters show how the pedagogical principles followed by Initiate Teachers can be applied in daily life.

The Epistemology and Psychology of Wisdom are present in the writings of John Garrigues. He made a unique contribution to the theosophical literature in a number of articles on the various aspects of one’s motivation along the Path. Such texts are scattered throughout the collection of the “Theosophy” magazine from 1912 through 1944 and in a few cases beyond that. The article “The First Step to Take” is an example among many.[1] In it we can read:

“A clean life involves purity, rectitude, chastity, and harmlessness, as well as absolute straightforwardness of conduct.”

The Writings of Garrigues

Garrigues is the author of the book “Point Out the Way”, which transcribes his lectures to students during the 1930s.[2] He wrote the best historical book so far on the first 50 years of the modern esoteric movement, “The Theosophical Movement – 1875-1925”.[3] His articles in “Theosophy” magazine would fill several volumes. In 1931, he started the annual ULT Day Letters, sent by mail every June to friends and associates of the ULT around the world. He was their main writer and editor up to his death in 1944. [4]

John wrote a book with fictional stories transmitting theosophical wisdom. It was published three years after his death, under the pseudonym of “Dhan Gargya”, and with the title of “From the Book of Images”.[5] Garrigues’ book of tales deserves careful study: in some of its stories he seems to have introduced minor difficulties to the text, so as to get the right kind of attention and concentration from the reader. By developing full attention one has access to the deeper meaning present in between the lines.

The JW Notes On Garrigues’ Life

Working in silence, Garrigues played a key role in the preservation and the spreading of true theosophy during the first half of 20th century.

Jerome Wheeler – the lifelong theosophist and editor who in 2000 founded “The Aquarian Theosophist” – sent us on 9 June 2005 a valuable account of John Garrigues’ trajectory.

“I never met him so can only tell you second-hand”, Jerome wrote. Before writing down his narration, he had gathered from older students and from the ULT Archives in Los Angeles basic and precise information on the life and work of Garrigues.

“John had only one arm”, JW writes. “When young he made exuberant plans to study in the West Point Military Academy, but had an accident during a hunting trip and his arm was amputated.” Karma has its own ways to prevent one from doing things to which “the door is closed”, and not all of such means are easy to deal with.

Born under the zodiacal sign of Virgo, Garrigues was a hard-worker and had a practical, down-to-earth, organized view of life.

“He was born September 12, 1868”, says Jerome Wheeler. “His wife was also dedicated to deep esoteric studies, which both started in July 1907 under the guidance of Robert Crosbie.”

The words “deep esoteric studies” are a reference to that which can be called “second section of the theosophical movement”.

In the early years of the theosophical effort, the “third section” was its public work. The members of the “second section” were either regular disciples, lay disciples, or aspirants to discipleship. The First Section was composed exclusively of high initiates in occult sciences or esoteric philosophy, that is, Adepts.[6] That means in the first years the Adepts or Masters were actual members of the movement.

An article says on p. 289 of “Theosophy” magazine, August 1919 edition:

“Robert Crosbie preserved unbroken the link of the Second Section of the Theosophical Movement from the passing of Mr. Judge in 1896, and in 1907 – just eleven years later – made that link once more Four Square amongst men. In the year 1909 the Third Section was restored by the formation of the United Lodge of Theosophists.”

John Garrigues and his wife were part of the pioneer group of inner studies in 1907, which would flourish as the ULT from 1909. When they helped create this deeper level of studies, in July 1907, Garrigues was 38 years old, and Crosbie was 58.

Starting from 1909 and up to Robert Crosbie’s death in June 1919, Crosbie and Garrigues were the two main leaders of the United Lodge. Due to his relationship with literature, Garrigues played a key role in the founding of “Theosophy” magazine in 1912, and in its editorial work.

Jerome writes:

“Crosbie and John are said to have been very different. John’s eloquence and flamboyant personality caused many people to think he was the ‘major founder’ when actually it was Crosbie. Robert Crosbie did not want attention drawn to himself. Crosbie changed John’s whole life. John was devoted to Crosbie very intensely, but Crosbie tended to stay out of the limelight. That’s why I have been told that many persons attending meetings and lectures thought JG was the center of the wheel.”

Raising Money for a Noble Cause

Most theosophists have to be active in the world of forms, as well as in the world of inner reality. Garrigues found it easy to deal with the external world and dedicated all his abilities to the theosophical Cause. He could raise considerable amounts of money, and his example is not the only one along that line.

Indian leader Mohandas Gandhi wrote in his Autobiography about his friend Raychandbhai, who was known as Shatavadhani, or “one having the faculty of remembering or attending to a hundred things simultaneously”.[7]

Raychandbhai had an intense professional life involving large sums of money, while keeping a 24 hours a day contemplative attitude towards life. “Raychandbhai’s commercial transactions covered hundreds of thousands”, Gandhi wrote. “He was a connoisseur of pearls and diamonds. No knotty business problem was too difficult to him. But all these things were not the centre round which his life revolved.” That centre was the meditation on the divine presence. Having a prodigious memory, Raychandbhai fascinated Gandhi for “his wide knowledge of the scriptures, his spotless character, and his burning passion for self-realization.” [8]

Garrigues had a similar ability regarding apparently contradictory factors such as universal wisdom and money exchange, or right physical plane memory and deep contemplation. He helped build the United Lodge in its inner and outer aspects at the same time.

JW writes:

“Garrigues was a financial genius whose specialty was to take bankrupt (or nearly so) companies and tell them what they had to do in order to return to health. He financed the Western part of the ULT building in Los Angeles out of his own pocket. He was broke more than once in the process of raising money for ULT.”

The testimony proceeds:

“John had a photographic memory. He remembered perfectly anything he ever read – including the S.D. His lectures were fascinating. He would use a very difficult passage of ‘The Secret Doctrine’ (from memory) and by the time he finished a many-layered explanation, even simple people felt they knew what it meant.”

Personal appearance is another field in which Garrigues showed an ability to combine inner and outer aspects of reality. Jerome Wheeler adds:

“When [ULT] lodge first began he always wore formal tuxedo with tails, then after many years he switched to a regular tuxedo. Even when I came on board in 1963, they still wore black suits. Nowadays we are totally informal!” As to transportation, “he began with a chauffeured limousine, then gradually changed to a regular car with a paid driver, and in later years rode with people to the lodge.”

A Lawyer in 90 Days

Garrigues was willing to face challenges at the professional front, as JW reports:

“At some point he initiated a law suit against of some fanatical Christians who were siphoning money from an oil company to their missionary efforts. At one point in the case he wanted to see the Books. He had an uncanny way of knowing the condition of a company simply from viewing the ‘accounting’. The Judge refused, on the grounds that he was not a lawyer and only legal counselors had the right to view evidence. He got a 90 day stay and walked back into the Courtroom as a lawyer! His son said he was hard to live with during those 90 days as he studied law books even while he was shaving!”

Life is probationary. The publication in 1925 of JG’s book “The Theosophical Movement – 1875-1925” was a success, but the Adyar Theosophical Society did not like this thorough account of the story of the theosophical movement. JW writes:

“When the Adyar T. S. threatened to sue the publisher of the ‘The Theosophical Movement – 1875-1925’, Garrigues wrote to the editor E.P. Dutton guaranteeing that the book was true and that he had data to back up every page on it. The Adyar Society did not go on with the law suit.”

In the 1930s, another challenge emerged when some group began misusing the name of the ULT and its Declaration. JW reports that Garrigues “initiated a court case on ULT’s behalf and won it; but during the process of court case someone asked who owned the ULT – and he was listed as the owner.”

The episode is narrated in “Theosophy” magazine:

“Early in 1937 two individuals who had at one time signed membership cards of the United Lodge of Theosophists incorporated under California laws an organization called ‘The United Lodge of Theosophists, Inc.’. In addition to this perversion of the original intent of the unincorporated association formed by Robert Crosbie in 1909, these persons adopted the original U.L.T. ‘Declaration’ and the form of enrolment by means of which each U.L.T. member becomes a registered associate. In order to protect the name of the United Lodge of Theosophists, and to prevent misrepresentation of its ideals, purposes, policy and teaching before the public, suit was brought against the corporation and its officers by a group of U.L.T. students. After numerous delays (…..) judgment was rendered March 25, 1938.”

The judgement said:

“The plaintiffs are entitled to a judgement against the defendants ….. and that they and each of them be permanently enjoined and forever be debarred from using the name ‘United Lodge of Theosophists’….” [9]

B. P. Wadia Was a Brother to Garrigues

As to family life, Jerome wrote:

“Not much of his outer life is known. Many of his relatives gradually came into the lodge, including his brother (who was a major speaker in San Francisco), his sister, and others. He was married and had one son.”

Garrigues’ wisdom was perceived by other theosophists, and JW’s 2005 report says:

“Mr. B. P. Wadia, after he was back in India, used to insist quite vehemently that John was one of those who KNEW. The European and Indian lodges of the ULT almost all originated from Wadia’s inner inspiration and from his financial support, too.”

While having a “flamboyant personality”, Garrigues also knew how to work as a team. In his well-known biographical essay on B. P. Wadia, Dallas TenBroeck wrote:

“[Mr. Wadia] used to say that Mr. John Garrigues and he were like two brothers, one could write the first part of an article and the other finish it and no discernible change was noticeable. Or they would share the burden of writing a series of articles, each writing alternating articles.” [10]

The Leadership of Example

Mere appearances were not the priority to JG, as JW reports:

“He was reputed to have a temper. I think this was superficial. He obviously was a warrior. He produced a ‘show’ if someone said stupid things. As uncontrolled anger destroys the astral, I think this aspect of his nature was an ‘outer performance’. Once during one of his talks someone in the crowd asked, if fishes could grow their limbs back why couldn’t he grow his arm back? This question, I was told, he answered in a very sweet voice with great patience, though the audience in general was shocked at such a question.”

Garrigues did pay attention to efforts to minimize the work of leaders by reducing them to the image of some personal imperfection.

In his article “The Leadership of Example”, he wrote:

“There are any number of books dealing with leadership, including studies of the world’s great military ‘leaders’, such as Napoleon, Alexander the Great, and Tamerlane, and treatises which analyze great literary figures like Poe, Dickens, Hugo, Flaubert. The trend in modern biography is to display the weaknesses of these personalities; and even to show in some cases that their very weaknesses elevated them to fame. Napoleon was only five-feet-three; hence, his ambition to dominate those who were taller! The shrivelled arm of the former Kaiser was the real impulsion behind his quest for glory.”

The article goes on:

“But what of spiritual leaders? Modern psychology honestly searches for some ignoble motive to ‘explain’ even great Teachers. Because no man known to the world is without some kind of imperfection, it is always easy to seize upon some attribute or quality as the ‘reason’ for greatness. Jesus was not a pure-blooded Jew. He was poor and bore the insults which come to the poor. So he made virtues of poverty and humility. He professed to despise distinctions of race, creed, sex, condition and organization – a mere ‘defence-mechanism’, we are told. But does this so-called ‘debunking’ of history explain why thousands of other men born in the same circumstances failed to attain the same greatness? Such theories neglect altogether the fact that the message of the world’s spiritual leaders is always the same. It is part of the work of the present cycle of the Movement to gather together the numberless spiritual teachings of the world and to show their identity.”

A few paragraphs later, one can read:

“How can a leader be great because of some weakness, coupled with a strong personal ambition to dominate? A true leader is great because he calls always to the spirit of man – because his faith in the omnipotence of spirit is supreme. His voice is universal, and all who hear it are raised in some measure to union with the truth.” [11]

Keeping People on Their Toes

JW says J. Garrigues “delivered the ULT Sunday evening lecture in Los Angeles every week until two years before he died, in 1944”.

He adds:

“Point Out the Way Study Class – which later became a book – probably occurred at the request of various students. Garrigues also handled all the correspondence of the external ULT lodge.”

It was JW who collected “Point Out the Way” into one manuscript.[12] In his main testimony on Garrigues, one can read:

“He spent much energy in trying to shock people into thinking, and once or twice put forth ideas which I relegated to Appendixes and labeled ‘dated!’.”

North-American theosophist Gabriel Blechman knew Garrigues personally, and was the first to write a public testimony on him. He reported that Garrigues was known to friends as “JG” and to young people in Los Angeles as “Uncle John”.

“My early memories of JG”, Gabriel said, “were from the periods before Theosophy School started, when he greeted the youngsters in a friendly way. He spoke with them at their level of understanding about various nature objects that were at hand in a glass display case or about anything that someone brought in. He fascinated us with low-key interesting things about all the kingdoms of nature. We hardly noticed that he was missing one arm. Other children and I looked forward to those pre-class sessions with JG. He never acted important, and we had no idea how vital he was to the work of the grown-ups. Looking back in later years, his attitude reminded me of the verse from ‘Light on the Path’ about the ideal student of occult lore: ‘That power which the disciple shall covet is that which shall make him appear as nothing in the eyes of men’.”

Gabriel wrote:

“JG liked to shock people out of detectable complacency, although I did not realize it at the time. He casually asked one time at lunch if I knew why in the old West the people who drank never mixed their drinks. I thought to myself, ‘Why would a theosophist talk so casually about something that we did not approve of?’ JG went on to explain why mixed drinks were not good. I don’t remember the explanation now, but I think it was correct and made some sense to those who drank alcoholic beverages. I remained puzzled for some time. The others took JG’s remarks in their stride since I think they knew his modus operandi well.”

“I heard that during his Sunday night lectures, which were presented in a quiet tone of voice, he often suddenly thundered out some words in a loud voice. When asked about this, he said it was to wake up the people that he may have put to sleep. This showed a good sense of humor as well as an awareness of audience response to what he was saying. His tactic was a kind of shock similar to that of his remarks to me on mixed drinks. He kept people on their toes so they could respond actively to what was going on.” [13]

There are always more than one viewpoint from which to look at any person. Another experienced student from Los Angeles kindly sent her views on JG’s life. In an individual message dated 17 September 2011, she wrote:

“No one in my family, all of whom knew, worked with, and loved JG well, ever thought he was difficult – far from it.”

John Garrigues died May 24, 1944, at 8:15 p.m. By then the result of the Second World War was clear and the triumph of democracy could be seen already as inevitable.

The victory of the United Nations against Nazism was declared in 1945 in the same day and month when, in 1891, H. P. Blavatsky had ended her mission: the 8th of May.

In the year of 1945, a cycle of seventy years was completed since the creation of the theosophical movement in 1875. With the victory of democracy, the United Nations headquarters was established in the same city where H. P. B. had founded the theosophical movement: New York.

NOTES:

[1] Click to see “The First Step to Take”. In another short article, Garrigues makes a thorough examination of the problem of despondency and the alternatives to it. Its original title is “The Dead Time”. It was first published at “Theosophy”, December 1920, pp. 46-47. It can also be seen in our websites under the title of “The Energy of Light and Hope”.

[2] “Point Out the Way”, by John Garrigues, is a typewritten and mimeographed / photocopied text of 211 pages which reproduces stenographic notes taken at informal talks on the book “The Ocean of Theosophy” by W.Q. Judge. The talks were delivered in the early 1930s at the Los Angeles Lodge of the United Lodge of Theosophists.

[3] “The Theosophical Movement – 1875-1925” (anonymous author), copyright 1925, E. P. Dutton & Company, 705 pp., USA.

[4] See in our associated websites the collection “The ULT Day Letters, 1931-1960”.

[5] “From the Book of Images and The Book of Confidences”, The Cunningham Press, Los Angeles, California, 1947, 192 pp. The authorship of “From the Book of Images” is stated by Mr. Dallas TenBroeck in the Files which he shared with friends in 2006. Internal evidence in the text of the work also clearly points to J. Garrigues.

[6] On the three sections the Movement, read the article “The Seven Principles of the Movement”. See also “Collected Writings” of HPB, TPH, volume II, pp. 500-501; “The Theosophist”, India, April 1880, p. 180, item X and others; and “Rules and Bye-Laws [of the Theosophical Society] as Revised in General Council at Bombay”, February 17, 1881, in “The Theosophist”, Adyar, June 1881, Supplement, especially item X.

[7] In a book published in 2009, Donald J. Trump ascribes to this function of mind the name of ‘multilevel focusing’. While discussing the nature of creative consciousness, Trump says: “The intersecting of ideas is when innovation will follow – thinking in musical terms while listening to your windshield wipers, or thinking of a hotel tower and condominiums at one time, or maybe watching a stone roll and imagining a wheel. Who knows what will result? Sometimes it will be fantastic and other times it won’t, but it gets the mind working in new dimensions that can sometimes prove fruitful. This can also happen without deliberately attempting to be innovative, so the other technique to employ – consciously and unconsciously – is to keep an open mind.” (“Think Like a Champion”, Donald J. Trump, with Meredith McIver, Da Capo Press, 2009, USA, 205 pp., see p. 08.) What Trump says about the action of an open mind is related to the ability to observe the world from the point of view of the Law of Analogy, which is discussed by Helena Blavatsky in “The Secret Doctrine” and other writings.

[8] “An Autobiography, or the Story of My Experiments with Truth”, M. K. Gandhi, Penguin Books, 1982, Part II, Chapter 1, pp. 92-93.

[9] “Theosophy” magazine, Los Angeles, May 1938 edition, pp. 335-336.

[10] Examine “B.P. Wadia, a Life of Service to Mankind”, by Dallas TenBroeck. See the paragraphs under the subtitle “1922-1927”.

[11] From “The Leadership of Example”, by John Garrigues. Published for the first time in “Theosophy” magazine, Los Angeles, December 1939, pp. 69-71.

[12] From the individual message dated 5 December 2005, item three.

[13] Click to read “My Memories of John Garrigues”, an article by Gabriel Blechman.

000

The above article was published in August 2012 and updated by the author in September 2017 and May 2024.

000

In September 2016, after a careful analysis of the state of the esoteric movement worldwide, a group of theosophists decided to form the Independent Lodge of Theosophists, whose priorities include the building of a better future in the different dimensions of life.

000

On the role of the esoteric movement in the ethical awakening of mankind during the 21st century, see the book “The Fire and Light of Theosophical Literature”, by Carlos Cardoso Aveline.

Published in 2013 by The Aquarian Theosophist, the volume has 255 pages and can be obtained through Amazon Books.

000